By Peter Finlay With appreciation to Paul Hamilton for assistance with Raymond Mays memorabilia, insight and photographs.

The editor and his wife went to the inaugural Hillclimb at Mount Coot-tha in May 2009 and were enthralled by the array of carsImage221 and drivers participating. It rekindled memories of warm languid days at Silverdale here in NSW, causing him to wonder about the roll of Hillclimbing in Historic Motorsport.

carsImage221 and drivers participating. It rekindled memories of warm languid days at Silverdale here in NSW, causing him to wonder about the roll of Hillclimbing in Historic Motorsport.

As far back as 1915 timed climbs of One Tree Hill, as it was then known, were conducted regularly. Boyd Edkins won the first event. Edkins, a well-known Sydney motor dealer, attained fame as an interstate record- breaker and Hillclimber. Also recognised as a competitor in 1915 and the winner in 1918 of the Mt. Coot-tha Hillclimbs was Frederick Eager, the “son” in the name E.G Eager and Son Pty Ltd, motor dealers in Brisbane. While discussing this article with Paul Hamilton at a literary luncheon for the release of Peter FitzSimons’ book on Charles Kingsford Smith we were reminiscing about Hillclimb events of the past wherein notable “name” drivers took part and added much glamour to the aura of the competition. Paul mentioned in a subsequent email:

“I think your article is a great concept for identifying the linkage with circuit events and the extent to which participation in both disciplines of the sport was, in past times, quite the normal practice. Most areas of modern life (banking included!) seem to have become so highly specialised that we can easily overlook simple lessons which have been learned elsewhere by those involved in activities closely related to what we are doing. That all seems like a backward step to me and I suspect that such trends within the finance industry may have contributed some to the world’s current woes. I am also quite sure that my first-lap performances on relatively cold tyres have always benefitted from my Hillclimb involvement!” Hear, hear, I say”

The 1967 Australian Hillclimb Championship event at Mount Panorama was one which Paul and I recall with great clarity for it was there that David McKay entered his Scuderia Veloce Repco-Brabham for Greg Cusack to drive. The “gun” sprint drivers of the day were present, led by Colin Bond in his supercharged Lynx Peugeot, with the Canberra road racer showing just how effective a circuit racing car could be, even when confined to the 1,123 yards (1,026 metres) of the original, longer, “Esses” course running the opposite way to normal circuit events. I was a mobile spectator in my Nota Formula Vee.

Until recently, the CAMS Manual of Motor Sport listed the winners of all Australian Championships. I must admit that Paul and I have shared a common and sadly unsated desire to assume the mantle of Australian Hillclimb Champion. Paul was denied his best opportunity in the 1975 Bathurst event while driving his venerable Elfin 600. My own missed chances occurred annually and somewhat monotonously between 1993 and 2002. Second places in 1993 (Mawer 004 Ford s/c) and 1996 (Pilbeam MP 62-Vauxhall) twice gave me the “bridesmaid’s garter award. Nice try, Pete, but no cigar. Typical of the split seconds which determine winners and losers in sprint events, my loosing margin was seven hundredths of a second. A bee’s dick, but it might as well have been seven minutes so far as the record books are concerned.

In the list of AHCC winners we find a staggering array of automotively- ambidextrous champions, many of whom were principally better known for their achievements on the track, rather than the hills. Amongst them are listed one World Champion driver, Sir Jack Brabham, plus two Australian Champion drivers – Lex Davison and Bill Patterson. The AHCC was instigated in 1938 when Peter Whitehead in the ERA was the victor. Frank Kleinig, well known for his exploits on Australian tracks in his Hudson, took out successive national titles in 1948 and 1949. Jack Brabham startled the establishment when he ran his Twin Special Speedcar at Rob Roy in 1951, while John Crouch (Cooper – 1952) and Reg Hunt (Vincent 1000 s/c 1953) took out the AHCC at the same venue. Again from 1954, the list for the following ten years contains names of drivers whose names were famed as much for their performances in other areas of motor sport as for Hillclimbing:

In the list of AHCC winners we find a staggering array of automotively- ambidextrous champions, many of whom were principally better known for their achievements on the track, rather than the hills. Amongst them are listed one World Champion driver, Sir Jack Brabham, plus two Australian Champion drivers – Lex Davison and Bill Patterson. The AHCC was instigated in 1938 when Peter Whitehead in the ERA was the victor. Frank Kleinig, well known for his exploits on Australian tracks in his Hudson, took out successive national titles in 1948 and 1949. Jack Brabham startled the establishment when he ran his Twin Special Speedcar at Rob Roy in 1951, while John Crouch (Cooper – 1952) and Reg Hunt (Vincent 1000 s/c 1953) took out the AHCC at the same venue. Again from 1954, the list for the following ten years contains names of drivers whose names were famed as much for their performances in other areas of motor sport as for Hillclimbing:

1954 Bill Patterson – Cooper J.A.P

1955-56- 67 Lex Davison – Cooper Vincent

1964 Ivan Tighe – Tighe Vincent

1965 Tim Schenken – White 500

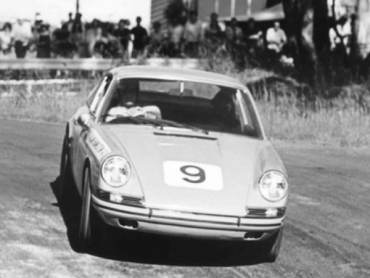

1966-71 Alan Hamilton – Porsche

1970-72-73 Paul England – Ausca

1975 Stan Keen – Elfin-MR5

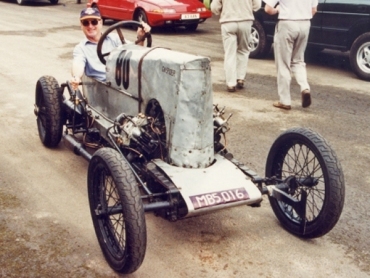

In this time-frame, to these names should be added those of drivers whose performances, asImage333 meritorious as they were,  tended to specialise in Hillclimbing: the great Bruce Walton (1959 through to 1963) in his Walton-Cooper, Ray White (1968 and 1969) White 1500 and 2000 respectively, Murray Bingham (1972) Bingham Cobra, Peter Holinger (1976, 1978, 1979) in his self-constructed Repco V8 engined Holinger…. probably the definitive minimalist Australian Hillclimb device and every bit in the mould of the famous British specials such as Basil Davenport’s G.N. Spider. Having said that, Ron Hay’s supercharged Honda 6-engined car, created in the 1970s, is still going strong now back in Ron’s hands. The stark, tube-framed car with a few sheets of aluminium to cover its “private parts” just gets on with the job very effectively.

tended to specialise in Hillclimbing: the great Bruce Walton (1959 through to 1963) in his Walton-Cooper, Ray White (1968 and 1969) White 1500 and 2000 respectively, Murray Bingham (1972) Bingham Cobra, Peter Holinger (1976, 1978, 1979) in his self-constructed Repco V8 engined Holinger…. probably the definitive minimalist Australian Hillclimb device and every bit in the mould of the famous British specials such as Basil Davenport’s G.N. Spider. Having said that, Ron Hay’s supercharged Honda 6-engined car, created in the 1970s, is still going strong now back in Ron’s hands. The stark, tube-framed car with a few sheets of aluminium to cover its “private parts” just gets on with the job very effectively.

It’s interesting to compare the cars too. In an interview a few years back Tim Schenken said to Patrick that his AHCC winning  White 500 was really nothing more than an overgrown go-cart with a JAP 500cc speedway engine in it. He couldn’t buy suitable tyres back then, but ended up using tyres from a wheelbarrow. On the sidewall of the tyre it had ‘maximum speed 5 mph’ and the thing probably did around 80 to 90.

White 500 was really nothing more than an overgrown go-cart with a JAP 500cc speedway engine in it. He couldn’t buy suitable tyres back then, but ended up using tyres from a wheelbarrow. On the sidewall of the tyre it had ‘maximum speed 5 mph’ and the thing probably did around 80 to 90.

England is the home of Speed Hill Climbing. “Mecca” to “Mad dogs and Englishmen” is the 1000-yard climb up the steep Worcestershire farm-yard hill road better known as Shelsley Walsh. This sacred site is one of the oldest motor sport venues in the world and the oldest to have been staged continuously (wartime excepted) on its original course, having first run in 1905 by the Midland Automobile Club. Fast forward to 1997 when Ivan Tighe and I were privileged to run at the 50th anniversary event of the Royal Automobile Club’s British hill climb championship in June of that year at Shelsley. The significance of the moment was not lost on us and the owners of our respective Pilbeams were most gracious in allowing us to use their cars. Steeper than most climbs, Shelsley exudes the essence of the discipline. The road rises 100 metres with an average gradient of 10.9% (1 in 9.14). Significantly the tarmac is only 3.66 metres wide at some points.

The winner of the first event was Ernest Instone (35 hp Daimler) who established the record time of 77.6 seconds for an average speed of 26.16 miles per hour (42.08 km/h). Not, you might say, a startling speed, but quite an achievement from a car the name of which evokes thoughts of a gentlemen’s staid carriage rather than a sporting machine.

speed of 26.16 miles per hour (42.08 km/h). Not, you might say, a startling speed, but quite an achievement from a car the name of which evokes thoughts of a gentlemen’s staid carriage rather than a sporting machine.

Indeed, in those days, the winner was established by the application of a formula based on power and the car’s ability to seat four people. The elapsed times were not announced to spectators! Some cars were hard-pressed to even reach the summit. By 1917 restrictions on specifications were dropped and so did the times, not unexpectedly. The first winner, after pure racing and sports cars were admitted, was a Vauxhall 30/98; the grand car which inspired Mays to begin his motor sport career at the Malvern hill in, of all things, a Hillman (great name for a hill climb car!) Mays went on to win the first two Royal Automobile Club British Hill Climb Championships in 1947 and 1948 on his “White Riley”; the car which became the starting point for the famous ERA marque.

The winner of the first event was Ernest Instone (35 hp Daimler) who established the record time of 77.6 seconds for an average speed of 26.16 miles per hour (42.08 km/h). Not, you might say, a startling speed, but quite an achievement from a car the name of which evokes thoughts of a gentlemen’s staid carriage rather than a sporting machine. Indeed, in those days, the winner was established by the application of a formula based on power and the car’s ability to seat four people. The elapsed times were not announced to spectators! Some cars were hard-pressed to even reach the summit. By 1917 restrictions on specifications were dropped and so did the times, not unexpectedly. The first winner, after pure racing and sports cars were admitted, was a Vauxhall 30/98; the grand car which inspired Mays to begin his motor sport career at the Malvern hill in, of all things, a Hillman (great name for a hill climb car!) Mays went on to win the first two Royal Automobile Club British Hill Climb Championships in 1947 and 1948 on his “White Riley”; the car which became the starting point for the famous ERA marque.

Pre-war, Mays had dominated many Shelsley events in his pair of Brescia Bugattis, “Cordon Bleu” and “Cordon Rouge”. Mays was also a highly competent Brooklands and Donington competitor who made several forays into European Grand Prix events, but his true love was hill climbing. A rather similar situation has developed over the years where drivers have commenced their careers in hill climbing and gone on to achieve fame in other disciplines. One S. Moss was given a start at Prescott hill climb in 1948 by our dear late Geoff Sykes. Moss covered himself with glory and “came of age” when he drove an HWM (which became the “Stovebolt Special in a later life) to third place in the Bari Grand Prix in Italy behind Giuseppe Farina and Juan Manuel Fangio.

Pre-war, Mays had dominated many Shelsley events in his pair of Brescia Bugattis, “Cordon Bleu” and “Cordon Rouge”. Mays was also a highly competent Brooklands and Donington competitor who made several forays into European Grand Prix events, but his true love was hill climbing. A rather similar situation has developed over the years where drivers have commenced their careers in hill climbing and gone on to achieve fame in other disciplines. One S. Moss was given a start at Prescott hill climb in 1948 by our dear late Geoff Sykes. Moss covered himself with glory and “came of age” when he drove an HWM (which became the “Stovebolt Special in a later life) to third place in the Bari Grand Prix in Italy behind Giuseppe Farina and Juan Manuel Fangio.

Ron Tauranac used one of his own cars to win the NSW State title in 1954 in his RALT 500 at King Edward Park. Hearsay has it  that it was much to the chagrin of Betty Brabham when Ron defeated her husband and a beautiful silver tea set was presented to the winner. Sir Jack is quoted as saying King Edward Park was the most demanding and best set-up Hillclimb in all of Australia. There are few motor sport venues which compare with that seaside park with its carnival atmosphere. I can concur with that, having won the annual event thrice in the little supercharged Mawer with a new outright record at its last outing. But, like many sports these days, the cost of competing at the premier level has escalated. One competitor has reputedly spent over $800,000 to tilt at the windmill without a national title to show for it. British hill climb champions and their cars have been brought in from England, yet none has yet managed to topple the locals.

that it was much to the chagrin of Betty Brabham when Ron defeated her husband and a beautiful silver tea set was presented to the winner. Sir Jack is quoted as saying King Edward Park was the most demanding and best set-up Hillclimb in all of Australia. There are few motor sport venues which compare with that seaside park with its carnival atmosphere. I can concur with that, having won the annual event thrice in the little supercharged Mawer with a new outright record at its last outing. But, like many sports these days, the cost of competing at the premier level has escalated. One competitor has reputedly spent over $800,000 to tilt at the windmill without a national title to show for it. British hill climb champions and their cars have been brought in from England, yet none has yet managed to topple the locals.

On the other side of the Pacific the Americans have awed themselves with their “Race to the Clouds” at the famed Pikes Peak Auto Hill Climb in Colorado. Here vehicles from all disciplines including motorcycles, trucks, sedans and open wheel cars have run against each other’s times on the sinuous road that winds to the summit at 14,110 feet (4,300 metres) above the Colorado plains. Since 1916 drivers and cars have come from all over the world to compete in the most challenging course through 156 turns over 12.42 miles (19.98 km) and climbing 4,708 feet (1,434metres) through sunshine, sleet, thunderstorms, wind, hail, fog and snow. It took the inaugural winner, Rea Lentz, 20 minutes, 55.6 seconds. It was his single moment of fame. The experience probably scared him off for life. Since then, men of the calibre of Barney Oldfield, flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker and multiple members of the Unser family have dominated the event. In 1988 Finnish World Champion Rally driver, Ari Vatanen, wowed the world with his skill and daring in the works Peugeot 405 T16 GR with over 600 brake horse power on tap, large aerofoils and four-wheel drive to claim the record in about half the 1916 time of 10 minutes 47.77 seconds. His efforts were immortalised in the 1990 award-winning cinéma véritié, short film, Climb Dance.

“Growing old is mandatory; Growing up is optional.”

This article is courtesy “The Oily Rag” Magazine from the HSRCA. Images of Alan Hamilton & Tim Schenken courtesy Autopics.

Please Enjoy Ari Vatanen in “Climb Dance”